November 1, 2018

I’m dressing for a dinner date!

With immense generosity, Martin, the Swiss Dad from the church group, has invited me to his house. Mum is not keen on dogs and I don’t know whether to leave Archie in the van. I also don’t know what to bring as a gift. Desert? Wine? I decide on flowers and we present them to the lady of the house. Granted, it’s not Ferrero Rocher but it seemed to do the trick. Archie is invited in and we leave him on the balcony because of the house cat.

I’ve been on the road for four months now; the smell of home cooking is heavenly: hand-picked mushrooms in a white sauce. We eat and talk. I’m interested in how life compares to Switzerland.

“We’ve given up some of the material things, for sure,” says Martin. “But we’ve gained some quality of life. More quality time with the boys, less stress.”

After desert, they clear away the dishes and spread guidebooks and maps over the table. They kindly show me some places I should visit; I note their recommendations: The Rose Valley, Shipka Pass, Plovdiv. The cat is AWOL, presumably sulking. Archie is duly invited in and the boys make a big fuss over him. He flops under the table while we drink coffee. We’re indebted to their generosity and I feel like I’ve made some friends here in Bulgaria.

SHIPKA PASS

The next day I head out to Shipka pass. It’s a remote, isolated spot atop the Balkan Mountains; In the late 19th Century, Russians joined Bulgarians here in fighting the Turks to liberate Bulgaria from the Ottoman Empire. A 30 metre high monument, a memorial to those that died for the cause, stands proud and erect on the hillside. Retired antique cannons surround it, surveying the breathtaking scenery of the valley below.

BUZLUDZHA

In contrast, a few miles drive away lies a structure which fills most Bulgarians with disdain. Buzludzha is a peak a few miles east of the Shipka pass; bold upon its summit lies a stark reminder of Bulgaria’s darker past. For here on this desolate hilltop in 1891, Dimitar Blagoev first assembled his secret socialist movement that led to the formation of the Bulgarian Social Democratic Party and ultimately the Bulgarian Communist Party. When they took power after the war, this was one of many monuments erected to celebrate the victory of Bulgarian socialism.

I get up at dawn to photograph the site. It’s very windy and I expect to be alone but I instead bump into a small film crew. They are students making a documentary about how this building reflects Bulgaria, how it symbolises the plight of their country. The young man behind the camera is Bulgarian, a student of Architecture in Paris. He applied to get access to the inside but was refused by the authorities.

He explains that his father’s generation are ashamed of this part of their past: “Over a short 40 year period, the Soviet regime nearly broke the Bulgarian spirit.”

He, however, was born after Bulgaria regained independence in the ‘90s; he has no memories, no baggage; he just thinks the structure is an amazing piece of architecture. We gaze for a while at its omnipotence in the steel-grey dawn light, an alien from another civilisation. Imagine it lit up at night, hosting a concert or festival! But the current political class have no ambitions to restore it. Instead a guard watches the site twenty four hours a day, circling the site hourly to detect intruders.

SHIPKA MEMORIAL CHURCH

With the whole of the day ahead of me, I drive to Shipka town where exists another kind of monument to a supreme power, the delightfully ornate church built in the early 20th century in the Muscovite style. In the courtyard stands a statue of a lady, head bowed in prayer, supplicant to God the Almighty. It too is dedicated to the soldiers that died for the liberation of Bulgaria.

VALLEY OF THE THRACIAN RULERS

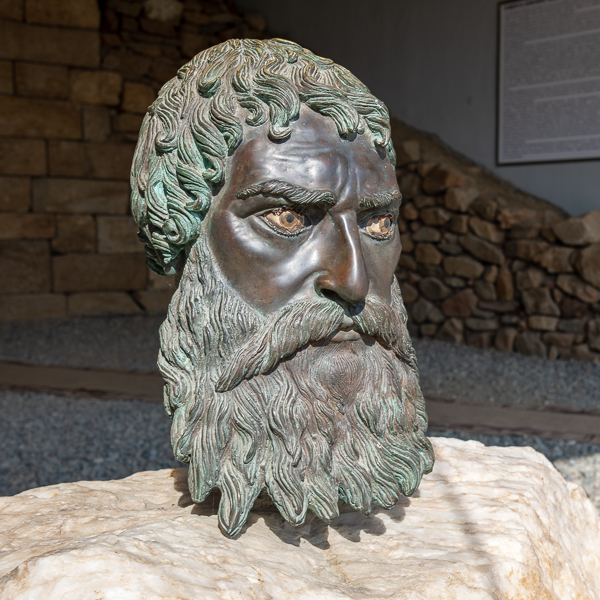

From here I head to the Kazanlak Valley, not for its world-famous roses which bloom in midsummer, but for its tombs. I learn that in ancient times, Bulgaria was once part of Thrace and in this region there exists over 1500 funeral mounds of which just 300 are researched. The Thracian Tomb of Kazanlak garners most attention due to its status of Unesco World Heritage site. I’m annoyed to discover that it’s only replica of the original. Better anyway is the The Tomb of Seuthes III, the king who revolted against Macedon in about 325 BC, after Alexander’s governor Zopyrion was killed in battle against the Getae (wikipedia). His formidable gaze continues to instil fear into mere mortals over two millennia later.

I’m discovering what a rich history Bulgaria has. Its beginnings can be traced back to antiquity when Aristotle taught Alexander the Great. Throwing off 500 years of Ottoman rule allowed the 3rd Bulgarian state to flourish in the late 19th century. Turbulent times in the first half of the 20th century culminated in Communist rule. 30 years later, the country is only just beginning to recover from these dark days.

I have to say that, like with Romania, I came to Bulgaria with preconceptions. And those preconceptions have been proved utterly wrong. Bulgaria is a beautiful place steeped in a wonderfully rich history; its people are remarkable craftsmen, with warm hearts and rich, deep souls.

Onwards to Plovdiv.