September 23, 2018

If you’ve ever seen Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, it’s hard not to have Johan Strauss’ most popular waltz on the tip of your tongue as you approach the city of Bratislava. With the New Bridge in your sights and the Blue Danube coursing underneath, your admission to the city is observed by a giant, eyeball-like UFO. You half expect it to reach into your van for your Schengen papers, gracefully dock with a nearby floating space station and blink red in negation of your arrival, uttering the words “I’m sorry Dave, I’m afraid I can’t do that” in cool English tones.

Perhaps this was the vision when politicians commissioned this piece of unique 60s communist-era architecture. Nowadays it lights up neon blue at night and you can pay a few Euros to enter the observation deck, or a few more Euros to eat in the fancy restaurant. It’s a sign of the city’s growing entrepreneurism.

I park up on the south bank and take a circular walk starting on the Apollo bridge. A DJ has set up some decks and is playing some tunes to a small gathered crowd. He nods to the beat as I take his picture. In the background The Danube flows like a river of bass vibration (thanks Underworld). It’s super-chilled. I like it when a city is on the cusp of something. Like Manchester in the 80s, or Leeds in the 90s, there’s a point where the freedom and exuberance of the people have not yet been tempered by rules and regulations. A point where a very palpable creative energy seems to gush from the very fabric of the city. A point where anything seems possible.

More people arrive on the bridge: girls drunk on cheap wine, laughing, high on life. It’s funny. When I speak to people in Bratislava they seem a little pessimistic. Wages are low, they grumble. We need more investment. I’m sorry to denude them of their fantasies but they are shocked to discover how much things cost in London. Be careful of what you wish for, I tell them. Higher wages, higher prices. Minimum wage earners pay half their wages for tiny box rooms In London for example. The problem with merely looking at the number on your payslip is that you ignore quality of life. These girls dancing to techno music don’t seem encumbered by the weight of having to work 30 hours just to pay the landlord.

By the river banks a band is playing Ska. The front man is hamming it up for the crowd, widening his eyes, pulling manic faces. Like a puppeteer, he stretches out his arms into the crowd, moving them to the beat of the drum. He sings in his native tongue but it doesn’t matter. Music has its own universal language. People of all generations are here: grandfathers bounce unselfconsciously to the unmissable tsss-ka beat; mothers cradle sleeping infants; teenagers pocket their phones for a couple of hours. It’s good old-fashioned fun, the kind you only seem to see at expensive festivals in the UK now. This is quality of life, surely. The ability to drive down to the river in the middle of your city, park up for free, drink a pint of beer for less than a Euro, and enjoy a free live band.

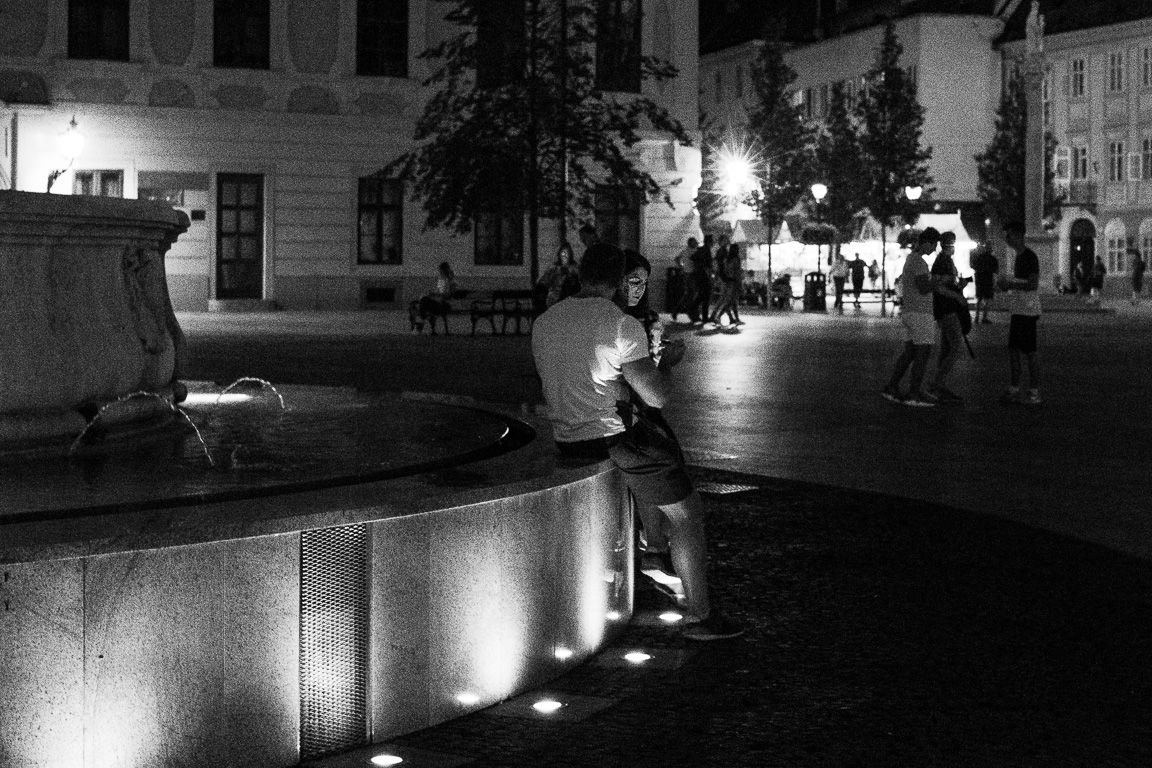

At night, the main street in the old town shines bright with restaurant lights. Duck down the side streets, however, and you are rewarded with dimly lit squares where couples canoodle on fountain edges, or darkened courtyards open up to reveal little wooden kiosks selling drinks or souvenirs. There are people milling around everywhere so it never feels unsafe. I sit down on a bench and watch a little girl by a backlit advertising board. She’s up on her tiptoes to see how far she can reach. Even at full stretch, the top is tantalisingly far. This brightly lit, just-out-of-reach, never-never land is the very essence of modern society. Forced coercion by rulers is but a memory and we do now have, at least the illusion of, free will. But this pernicious and subtle grooming, especially of the very young, to fall into line is, to me at least, one of the great tragedies of the 21st century.

I suppose it’s human nature to want more. Things could be better, but things could be much worse. At a bar exhibiting photographs from the dark days of the communist era, I talk to the Bulgarian barkeeper. His retired parents, he tells me, live on 100 Euros per month between them, 30 of which is spent on his mother’s medicine. “Bulgaria is a poor country,” he say. “In Greece, where I worked, yes the wages were low but the cost of living was also low.”

He was in Greece when their economy collapsed. He thinks the Germans should have shown the same mercy they themselves were afforded after the war. I hear this a lot on the East side of Europe. They feel like they’re scrabbling for the crumbs after a 50 year feast. They think the dice are loaded.

“This is my brother’s bar,” he tells me, “But I’m going to set up my own soon. Not in the old town, it’s too expensive. Start small and build up.” I wish him luck. The dice are always loaded but sometimes you get lucky.

In the morning I’m struck by crowds of people flocking over the Apollo bridge, moth-like, towards the bright light of a large American company’s logo. It’s surely a sign that Bratislava is fast becoming a post-communist, capitalist state. Be careful what you wish for guys.

Lovely descriptions and metaphors